|

| Pawel Poljanski's legs at the Tour De France |

Her obesrvation is accurate. I actually lift weights twice a week and even though I can squat 90 kg, my thighs are still skinny.

I also explained to her that it is better to be strong than have big muscles. Weight training can make you stronger and your muscles bigger. They are both related since bigger muscles are usually stronger. However, they are not identical. You can get stronger without adding muscle bulk.

This happens when the signaling from your brain to your muscles become more efficient and how effectively your muscle fibers are recruited. You can add muscle without getting stronger, this typically happens when you gain weight.

Strength is also a much better predictor of cognitive performance than muscle mass. Storoschuk and colleagues (2023) studied 1424 adults above 60 years of age between 1999 and 2002 in a health and nutrition examination study (NHANES). These subjects had DEXA scans to assess body composition, leg strength tests, a digit symbol substitution test (cognitive test) and questionnaires that assessed physical activity habits. The DEXA scan is used to determine how much muscle one has in their arms and legs and fat-free mass index (FFMI), which shows total muscle to height.

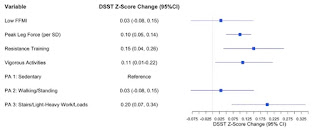

The figure above presents the benefits of different variables on cognitive performance. The farther on the right each square is, the greater the cognitive benefits. You can see that low FFMI (low muscle mass) has no significant effect on cognitive scores, while peak leg force (a measure of strength) definitely have a significant benefit. Those who did resistance training (or weight training) for at least once a week has an even stronger effect.Strength explained about 5 percent of the variance in cognitive scores, while muscle mass explained only 0.5 percent. Low strength levels raised the risk of premature death, but low muscle mass did not. In contrast, another study by Tessier et al (2022) found that low muscle mass predicted more rapid cognitive decline over a 3 year follow up period, after accounting for differences in strength. Perhaps it would be premature to conclude that muscle mass (being big) does not matter.

Confused? Storoschuk et al (2023) explained that there is a difference between the muscle you get from physical activity and muscle you get in the process of gaining weight. Greater muscle mass may just be a larger body size rather than greater strength, which does not seem to translate into protection from cognitive decline and other health benefits.

Moreover the conflicting results from the 2 studies are possible due to different popolulations, different cognitive tests and different sample sizes.

My take on this? It is good if you have big muscles and I will still lift weights twice a week to at least maintain and avoid losing what I have. Getting stronger is much better, and that is the main reason why I do weight training. Even though I do not seem to gain muscle I am able to increase the reps and quality of the exercises I perform.

So, to ward off cognitive decline, strength training is just as important as aerobic exercises.

References

Tessier A, Wing SS, Rahme E et al (2022). Association Of Low Muscle Mass With Cognitive Function During A 3-Year Follow-up Among Adults Aged 65 To 86 Years In The Canadian Longitudinal Study On Aging. JAMA Netw Open. 5(7): e2218826. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19926

Storoschok KL, Gharios R, Potter GDM et al (2023). Strength And Multiple Types Of Physical Activity Predict Cognitive Function Independent Of Low Muscle Mass In NHANES 1999-2002. Lifestyle Med. 4: e90. DOI: 10.1002/lim2.90

No comments:

Post a Comment